The Self is Not Just a Network of Beliefs and Desires: Using Lived Experience and the Minimal Self to Argue with Richard Rorty

- Andrew Field

- Dec 4, 2025

- 9 min read

A somewhat long time ago (1989), in a book few people seem to read today, Richard Rorty argued in Contingency, irony, and solidarity that it would never be possible to unite art and justice, literature and moral agency, together at the level of theory. “But there is no way to bring self-creation together with justice,” he wrote. For Rorty, self-creation was “private, unshared, unsuited to argument.” Justice, on the other hand, was “public and shared, a medium for argumentative exchange.” As someone living with schizoaffective disorder, for whom the relationship between the public and private was a vexed thing, this argument always struck me as too neat. Were art and ethics fated to forever revolve in their own autonomous dimensions, the upshot of Kant’s differentiating the value spheres? But wasn’t one of the most ancient of concepts in the Western world associated with art - catharsis - involved with dynamics both aesthetic and ethical, through a form of cognitive-affective clarification? For I had lived through three episodes of psychosis, the third of which lasted three years, and still I returned to the reading and writing of poetry, and the drawing of cartoons, as means through which I attempted to make sense of things; and this sensemaking, as both need and act, struck me as private and civic, as cathartic, in way that Rorty’s analysis seemed to elide.

What then was the relationship between art and moral agency? How could we talk about this? Did it make a difference that Rorty was emphasizing the relationship between art and justice at the level of theory?

It seemed that some answers lay in my experience of living with schizoaffective disorder. How so? Louis Sass has written convincingly of the way in which psychosis can be interpreted helpfully through the notion of solipsism. When one is psychotic, one begins to involuntarily deny, to make opaque, the shared public world. One projects onto this world one’s delusions and hallucinations, and then calls this autotelic world the world, when it is in fact a projection. You could say, then, that psychosis strips us of moral agency, by denying us the opportunity to dwell in the shared world. How does art fit into this picture? I think art, when we are in recovery, has the power to remind us of our moral agency, and in that sense, works to restore moral agency. But this in turn suggests a kind of sociality of the private self that Rorty’s argument denies. Art restores a virtual version of the shared social world. In doing so, it gives us something to chew on, to think about, to practice on. As Martha Nussbaum argues, art makes us a participant and friend in things. In clarifying our thoughts and feelings, and giving us catharsis, art commits us with greater passion and foresight to our obligations. It thereby gives us greater opportunities to experience what Robert Brandom has called “reconstructive recollective rationality,” essentially the ability to understand our lives autobiographically through experience - and what is denied to us when psychotic, which works to distort this ability.

When Rorty draws a split between the public and the private, he is arguing that philosophical reconciliation is impossible, because each sphere focuses on different values. But he is not arguing that such a reconciliation is impossible to achieve politically. Still, there seems room here to trouble this distinction further - not to refute Rorty formally, but at least to make his distinction less rigid. One way to do this is to focus on what is called in the psychological and philosophical literature the “minimal self.” The minimal self, as theorized by Dan Zahavi, is pre-reflective, and is related to the givenness of experience, the what-it-feels-like-to-be-me. I think this sense of the minimal self is incredibly important, in that it fills in a picture of the narrative self that Rorty was often propounding. Let me show how Zahavi’s minimal self fills out this picture, after which we can discuss the sociality of self. In “Non-Reductive Physicalism,” in Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth, Rorty writes,

But once we drop the notion of “consciousness” there is no harm in continuing to speak of a distinct entity called “the self” which consists of the mental states of the human being: her beliefs, desires, moods, etc. The important thing is to think of the collection of those things as being the self rather than as something which the self has. The latter notion is a leftover of the traditional Western temptation to model thinking on vision, and to postulate an “inner eye” which inspects inner states. For this traditional metaphor, a non-reductive phsyicalist model substitutes the picture of a network of beliefs and desires which is continually in process of being rewoven (with some old items dropped as new ones are added). This network is not one which is rewoven by an agent distinct from the network - a master weaver so to speak. Rather, it reweaves itself, in response to stimuli such as the new beliefs acquired when, e.g., doors are opened. (123)

What’s problematic about this passage, of course, is exactly what Zahavi points out - that Rorty’s understanding of self here is impoverished, because it is lacking a picture of the self that is more than just a web of beliefs, desires, and moods. Rorty draws a circle, but what he is missing is the subject in that circle, and that subject does “inspect mental states,” and does have an experience of pre-reflective mineness when it comes to one’s own experience. The self is not just a network of beliefs and desires. My own experience living with schizoaffective disorder serves as an argument against this argument, for I experienced a radical change in my pre-reflective sense of what it felt like to be me, and when I began to recover from my episode, this pre-reflective sense changed again, into something we could argue, in Heideggerian terms, was more authentic. When Rorty observes a strict division between the public and private, he is, in a strange sense, attempting to demarcate the boundaries of the self when his picture of that self does not involve or engage with the minimal self. For there has to be a boundary between the public and private, in the sense that what is pre-reflectively given to me, as the minimal self, is different empirically, in terms of content, than what is given pre-reflectively to another self. Because Rorty does not speak of the minimal self, he needs something else to push back against the private, and he does so with his public/private theoretical split. But again, this strategy for bounding a self that is merely a network of beliefs and desires is confused and confusing.

Psychosis is an involuntary form of ethical blindness, and therefore tragic. But it is an ethical blindness because there is a minimal self, that is also an interpersonal self. This is a place where things also get confusing, for how could a pre-reflective sense of what it is like to be me also be interpersonal? What is the relationship between the interpersonal self and the minimal self? So often in the course of my readings I’ve been presented with pictures of the self as a kind of tapestry of other selves - I’m thinking right now of Harold Bloom’s anxiety of influence, for example, where the self as self, the poet qua poet, is made of other poets. Yet this too downplays the role of the minimal self. Let me speak to this from personal experience, and do so through a cartoon I drew when I was psychotic and living without insight. The cartoon was an attempt, during my third episode, at sensemaking, to make sense of my thinking and feeling. Later, when I read it when I recovered, it seemed I was trying to share the way in which the world had become illegible, though legible in a different way. It’s about the way in which the social public world itself was continually deferred. It is an argument for the minimal self, but also for the minimal self in relationship to the interpersonal self, in a way that seems to loosen Rorty’s rigid distinction. Here’s the first page of it:

I wonder if the strange malleability of the speaker’s facial features had something to do with my inability to really see others as others. It was like a kind of anchor that was denied me. The speaker of the cartoon is invested with the idea of “making the visual world asemic.” Why? Asemic means “without specific semantic content,” and is often invoked in works of art where a kind of wordless script that approximates the visual look of language is written or drawn. For example, this work, by Cecil Touchon.

It is something that we both read and do not read; it contravenes our expectations for language, so that what we see is both alien and familiar. A wrench has been thrown in our sensemaking activity, and we are therefore forced to pivot and see in a different way. What we see is strangely opaque, is a form of meaning-deferral. And yet, in its own right, it is beautiful.

I think I wished to make the visual world asemic because at that point in my psychotic episode the world had become almost asemic, had become unintelligible. But the fact that the world could become unintelligible to me, while remaining intelligible to others, suggests that Rorty’s notion of the self lacks a kind of sharpness, a clarity. What was happening was that my minimal self was being transfigured by my illness. This was not just a reweaving or reconfiguration of a network of beliefs and desires. This was a torquing of the minimal self. To invoke another Rortian term critically, this was more than a redescription. It had greater moral consequences, consequences that were as much idiosyncratic and ironic as they were public and shared. Psychosis causes the autobiographical self, the historical self, to diminish and fade, but it does not diminish or fade the minimal self. The self becomes solipsistic - a self so taken by what Clara Humpston has called “ontologically impossible experiences” that the world as the world, as the texture of significances that we live and breathe everyday, is eclipsed, is replaced by a different texture that is private in the sense of not shared. Is the solipsistic self the narrative self or the minimal self? Both, I would think.

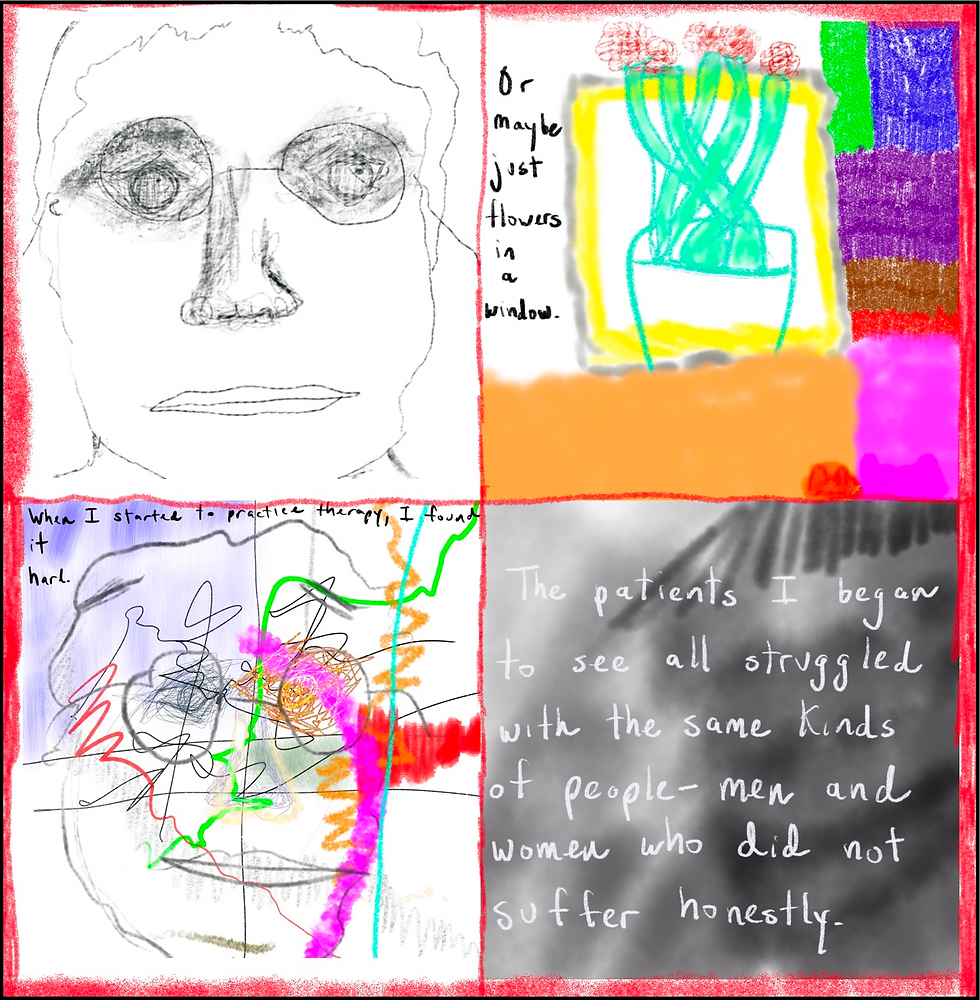

In a different cartoon I drew, around the same time, a therapist is speaking, and her face keeps changing in the different panels in ways I find now to be evidence of the instability of madness, and its simultaneous and consequent desire for stability. It is evidence of the way in which the minimal self is affected in madness. It is also a strange example of the formlessness of madness trying desperately to make meaning, even as madness is, in a sense, a deferral of meaning. Like slipping in quicksand. Or we can say it is a search for moral agency, even as one’s moral agency is being eclipsed. To understand this cartoon, you have to notice the chaos of the style as much as the conventionality of its narrative - a conventionality that I think I longed for, having been living for months then in a state of mind that felt deeply chaotic. In a different part of the cartoon, I even begin to talk about “suffering honestly,” something I was obsessed with then, perhaps because I couldn’t see that my own suffering wasn’t “honest,” in the sense that I did not think I was mad. Yet I cast myself into the role, not as the patient, but as the therapist. In the cartoon you can see at the level of style an instability, even as, at the level of content, it strives to find stability through the motif of therapy and healing.

Other drawings I drew then evidence a similar way in which style and content seem to clash in strange ways, as the minimal self is affected, and as public and private become entangled in bewildering ways. I used vivid and bright colors, because my mania then made the world’s color brighter. Matthew Ratcliffe, who offers a cogent picture of the minimal self as also an interpersonal self, has argued that imagination is in a sense at the heart of madness, as delusions can be construed as a confusion of imagination with belief, and as hallucinations can be construed as a confusion of perception with imagination. These cartoons seemed to me then to voice what I was experiencing, but in an indirect way, as I was not aware objectively that what I was experiencing was madness. In one, an older man greets the viewer; in a second, a woman brings a man a tray of things. Both seem like attempts to find something everyday that I could hold onto, even as the everyday texture of significances was denied me. In a third drawing, I tried to recreate the moment after David slayed Goliath. This seems to me now also an attempt at sensemaking, when my own ability to make sense was gummed up.

I think these drawings evidence an idiosyncrasy that might help to capture Rorty's sense of self-creation, but they occurred in a context - madness - that has an irreducible social aspect. So, to end, while formally I can't totally refute the difference between the private and public - and this is to Rorty's credit, who I have been learning from for 20 years now - Rorty's account of the self does need to be filled out more, made thicker. Accounts of lived experience, as well as the notion of minimal self as Zahavi characterizes it, and as Ratclifffe assists in emphasizing its interpersonal components, can help us do so. Art in recovery restores moral agency. When we are sick, I suppose it does something analagous to Justin Garson's notion of "madness-as-strategy," which is to say, it helps us to cope and adapt, if not to totally restore the social public world, or return our authentic minimal self to us.

Comments